In 1960, psychologist Peter Wason conducted a series of experiments to test a theory.

In the experiment, he presented his subjects with a series of three number and asked them to determine the rule for which they followed.

Based on the presented series, subjects could propose other series of numbers to see if they also satisfied the rule. After they were satisfied with their tests, they could propose what they believed the rule was.

Wason’s goal was to better understand how people collected evidence in support of a belief. The series of numbers Wason presented to subjects was 2-4-6.

Naturally, the first assumption was that the rule was a series of increasing even numbers, yet whatever their initial hypothesis, they only offered tests that fit with their hypothesis.

Subjects proposed a number of other examples to test their assumptions:

8-16-24 (increasing even numbers)

4-8-12 (average of first and last equals middle)

8-10-12 (increasing by value of 2)

All of these passed the test and were valid for the rule. Subjects almost always then proposed a rule that supported their initial assumptions. The thing is, they were always wrong.

The actual rule was simply increasing numbers in general. It didn’t matter if they were even or odd, incremented consistently or averaged. Each subsequent number simply had to be larger than the previous value.

The issue that subjects faced time and time again, was that they never tested a series of numbers that disconfirmed their initial assumptions.

It is the peculiar and perpetual error of the human understanding to be more moved and excited by affirmatives than by negatives.Francis Bacon

This is confirmation bias.

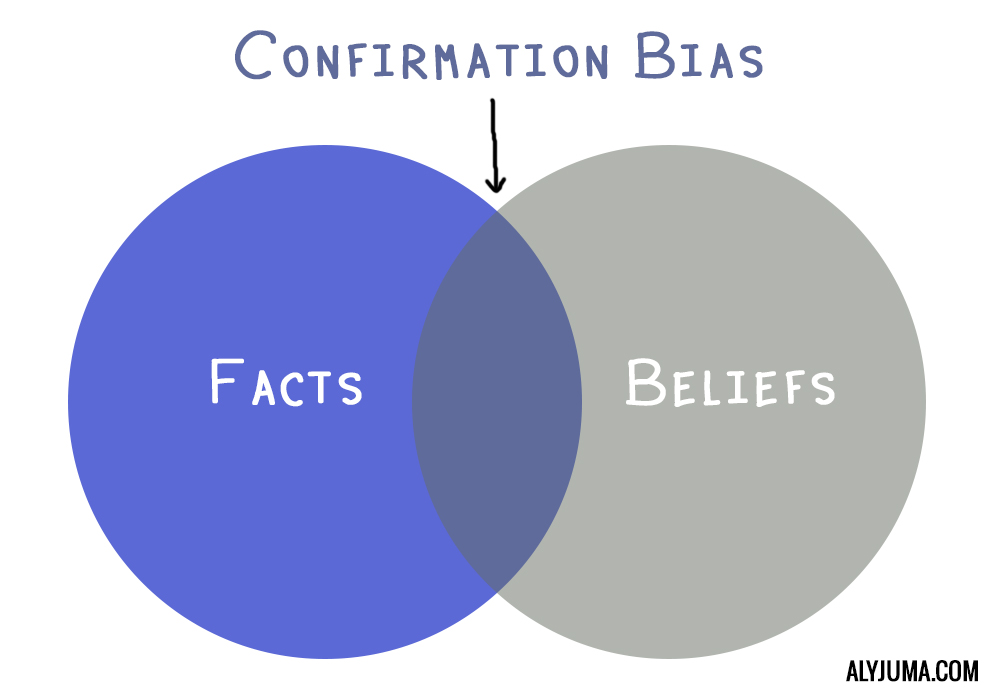

It is a form of thinking where you take notice or seek out information that confirms your beliefs, rather than what contradicts them. There are two distinct areas. First, there are facts, which are the truths around any subject as far as we know them. Second, there are our personal beliefs or what we believe to be true. Where these two overlap is where confirmation bias can occur.

There are two distinct areas. First, there are facts, which are the truths around any subject as far as we know them. Second, there are our personal beliefs or what we believe to be true. Where these two overlap is where confirmation bias can occur.

The problem is, we tend to ignore all the other facts that may dispute our beliefs. Why does this happen? It seems to be related to how our mind retrieves information both cognitively and emotionally.

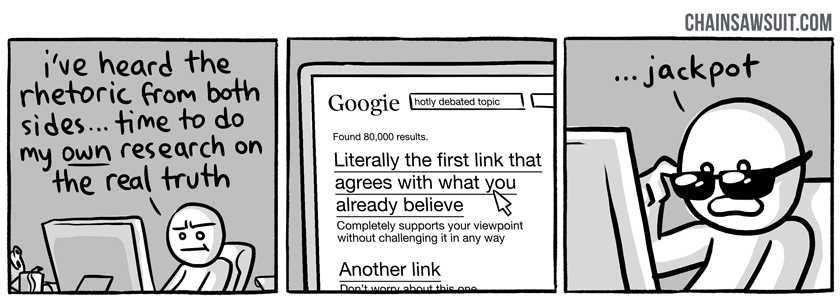

From a cognitive stand point, we tend to select information that is easy for us to retrieve. In this way, we grab on to the first idea we have and see if it works. If it does, we stick with it because it is the path of least resistance.

For example, subjects that believed even numbers were relevant in the experiment above, simply stuck with that idea because it came to them first.

Then there is the emotional standpoint, where we simplify prefer to be right rather than wrong. We want pleasant thoughts over unpleasant ones. In this way, we naturally want our beliefs to be truth because that makes us right. We stick to our guns in the worse way possible. Confirmation bias can clearly get the best of us, so how do we overcome it? We have to get in the habit of proving ourselves wrong.

Confirmation bias can clearly get the best of us, so how do we overcome it? We have to get in the habit of proving ourselves wrong.

It’s not enough to find information that backs your point of view. You also need to try and find information that refutes it. You need to play devil’s advocate and argue against your personal beliefs.

By doing so, you’ll be able to clearly see the flaws in your thinking and not fall into the trap of confirmation bias.

As they say, ignorance is bliss, but knowledge is power. Take the time to prove yourself wrong.