Herman Melville had his wife chain him to his desk so that he was forced to finish his epic novel Moby Dick. Victor Hugo locked his clothes away, so he couldn’t leave his house when he was under deadline to finish The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Writers do some crazy things to get their novels completed, but it also points to a more general truth about everyone.

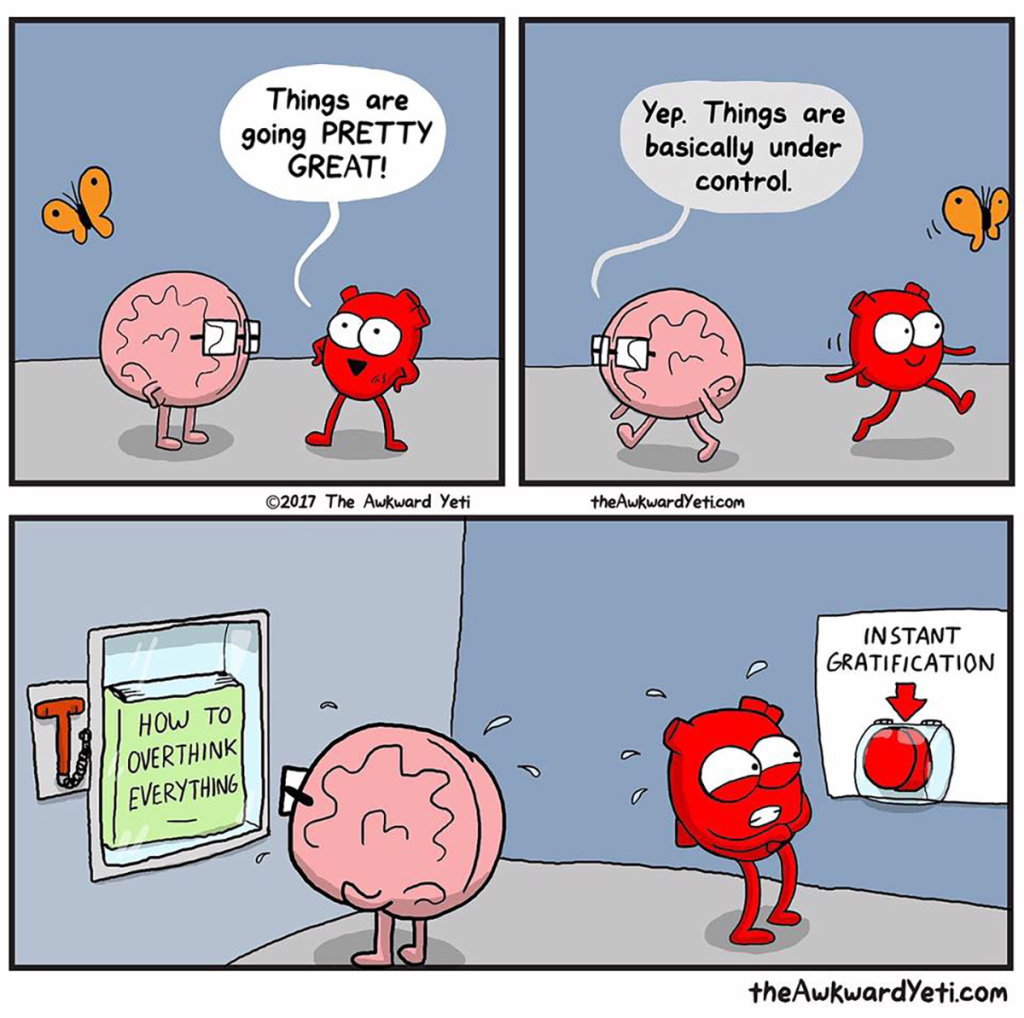

We all know what we ought to be doing in work and life, yet we have mastered the art of avoiding it, as best we can. We know what we should do, but we don’t do it anyways. What’s happening here?

There’s actually a name for this phenomenon where we often show a weakness of will, it is called akrasia. Akrasia roughly translates to the state of acting against one’s better judgment. It is when we know what to do, but we don’t do it anyways. It sounds like insanity, but it’s part of everyday life.

The History of Akrasia

The term comes from the Ancient Greek word ἀκρασία, which means “lacking command (over oneself).” It was also the subject of conversation for several philosophers back in the day, including Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle. In Plato’s dialogue Protagoras, Socrates asks a simple question: if someone accepts a certain behavior is the best course of action, why would they do anything else?

Plato and Socrates essentially believed that akrasia does not exist. That it was a moral defect, if one made such decisions, believing that “no-one goes willingly towards the bad”. Aristotle, on the other hand, takes a more nuanced approach to the idea.

He recognizes that there are two types of akrasia. One is driven by passion, which may cause a lapse in reason or irrationality. People can be overcome by emotion and make poor decisions.

The second type of akrasia is caused by weakness. In contrast to the passionate person, the weak-willed individual fully understands the consequences, but still goes against their better judgment.

Ultimately, Aristotle acknowledges that akrasia exists and is largely based on opinion, not fact. If we are misaligned, it is because of our opinions, not our reasons. Following this idea, akrasia is a lack of power over oneself, but not all akratic decisions exhibit a weakness of will.

…no one goes willingly towards the bad.Socrates in Plato’s Protagoras

One can be akratic, and act against their interest, but still be strong-willed. For example, I’m certainly akratic when it comes to my diet. I know that being vegan would be better for me in terms of health, ethics, and environment, but I am not vegan. I choose to eat meat all the same. This doesn’t make me weak-willed. If I chose to be vegan and still wasn’t, that would be a weakness.

In this sense, intention determines weakness of will, but it is not required for akratic behavior. The core attribute is simply going against your better judgment, whether you want to or not.

Why It Matters

This may sound very similar to procrastination, but it’s really a deeper issue. When you procrastinate, you decide to do something, but then you continuously put it off. The difference to akrasia is a subtle one, but very important. In akrasia, you never take action at all. You don’t try a bit, you simply ignore the facts of the matter and do the opposite.

Akrasia is one of the biggest barriers to happiness, success, growth, and progress. It is knowing what you should do, but don’t do.

When you have one more drink when you know you should call it a night. When you stay up late watching TV when you should be asleep already. When you should give up smoking, but just have to have another cigarette. When you should be working out every day, but make excuses instead. Akratic behavior is all around us.

It occurs in little moments throughout your day, but these moments compound and have a massive impact on your life.

Why does this happen?

One explanation is “time inconsistency”. Time inconsistency is a tendency to value immediate rewards over future rewards. Most of our goals will be valuable to achieve for our future selves, but not in any given moment. In these moments, we often prefer the instant gratification, the immediate value, so we don’t act. We put off our goals, we bury our judgment, and we give into weakness.

In these moments, we often prefer the instant gratification, the immediate value, so we don’t act. We put off our goals, we bury our judgment, and we give into weakness.

How do you overcome akratic behavior?

How do you solve akrasia? There are two strategies for attacking it: art and ritual. When it comes to art, it’s all about emotion.

Art isn’t meant to give us new ideas, rather they compel us to embrace the ideas we are already intimate with. To take action, to realize what we know and act upon it, rather than letting it passively exist in our minds.

The goal of art, which includes books, music, movies, paintings, design, photography, and more, is meant to empower the knowledge we possess already and hopefully inspire us to act on it. It is to stir feelings that force us to make the changes in our lives that we already recognize we need to pursue.

Ritual is the other approach, which is founded on structure and repetition. Building good habits, routines, and behaviors help us avoid the pitfalls of akrasia, as it is already embedded into our lives. We train ourselves to do the things we know we should do so that we are less inclined to give in to our weakness of will. Ritual trains sequence, follow through, and results. More than just recognizing what is right, it reinforces it every day.

Experiencing art and embracing rituals are the two paths we can leverage to move beyond akrasia.

What it lies in our power to do, it lies in our power not to do.Aristotle

We crave instant gratification and immediate rewards. We focus on the present and often forget our future. We go against our better judgment in life, far more often than we’d care to admit, but we can correct it all. We can learn to embrace our knowledge and reason, it’s a matter of self-discipline.

Aristotle in his exploration of akrasia also defined its antonym, which is enkrateia, which means in power of oneself. This is what we all need to strive for to unlock our potential and live better lives. Art and routine can help you get there, but ultimately it comes down to your will and how it impacts your decisions.

Choose to follow your judgment, not ignore it.